Curtis LeMay

| Curtis Emerson LeMay | |

|---|---|

| November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990 (aged 83) | |

.jpg) |

|

| Nickname | "Old Iron Pants", "Bombs Away" LeMay |

| Place of birth | Columbus, Ohio, United States |

| Place of death | March Air Force Base, California, United States |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | United States Air Force United States Army Air Forces United States Army Air Corps United States Army Ohio National Guard |

| Years of service | 1928–1965 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Twentieth Air Force Strategic Air Command USAF Chief of Staff |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross Army Distinguished Service Medal (3) Silver Star Distinguished Flying Cross (3) Air Medal (4) Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) Légion d'honneur (France) |

| Other work | Politician, candidate for U.S. vice president |

Curtis Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990) was a general in the United States Air Force and the vice presidential running mate of American Independent Party candidate George Wallace in 1968.

He is credited with designing and implementing an effective, but also controversial, systematic strategic bombing campaign in the Pacific theater of World War II. During the war, he was known for planning and executing a massive bombing campaign against cities in Japan. After the war, he headed the Berlin airlift, then reorganized the Strategic Air Command (SAC) into an effective instrument of nuclear war.

Contents |

Early life and career

Curtis Emerson LeMay was born in Columbus, Ohio, on November 15, 1906. His father, Erving LeMay was at times an ironworker and general handyman, but he never held a job longer than a few months. His mother, Arizona Carpenter LeMay, did her best to hold her family together. With very limited income, his family moved around the country as his father looked for work, going as far as Montana and California. Eventually they returned to his native city of Columbus. LeMay attended Columbus public schools and studied civil engineering at Ohio State University. Working his way through college, he graduated with a bachelor's degree in civil engineering. While at Ohio State he was a member of the National Society of Pershing Rifles and the Professional Engineering Fraternity Theta Tau. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Air Corps Reserve in October 1929. He received a regular commission in the United States Army Air Corps in January 1930. On June 9, 1934, he married Helen E. Maitland (died 1994), with whom he had one child, Patricia Jane LeMay Lodge, known as Janie.

LeMay became a pursuit pilot and, while stationed in Hawaii, became one of the first members of the Air Corps to receive specialized training in aerial navigation. In August 1937, as navigator on a B-17, he located the battleship Utah in exercises off California, after which the aircraft bombed it with water bombs despite being given the wrong coordinates by Navy personnel. In May 1938 he navigated B-17s over 610 miles (980 km) of the Atlantic Ocean to intercept the Italian liner Rex to illustrate the ability of airpower to defend the American coasts. War brought rapid promotion and increased responsibility.

When his crews were not flying missions they were being subjected to his relentless training, as he believed that training was the key to saving their lives. LeMay was widely and fondly known among his troops as "Old Iron Pants" throughout his career.[1]

World War II

When the U.S. entered World War II in 1942, LeMay was a major in the United States Army Air Forces, and the commander of a newly created B-17 Flying Fortress unit, the 305th Bomb Group. He took this unit to England in October 1942 as part of the Eighth Air Force, and led it in combat until May 1943, notably helping to develop the combat box formation. He led the 4th Bombardment Wing and was its first commander when it was reorganized into the 3rd Air Division in September 1943. He often demonstrated his courage by personally leading dangerous missions, including the Regensburg section of the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission of August 17, 1943. In that mission he led 146 B-17s to Regensburg, Germany, beyond the range of escorting fighters, and, after bombing, continued on to bases in North Africa, losing 24 bombers in the process.

The heavy losses in veteran crews on this and subsequent deep penetration missions in the autumn of 1943 led the Eighth Air Force to limit missions to targets within escort range. Finally, with the deployment in the European theater of the P-51 Mustang in January 1944, the 8th Air Force gained an escort fighter with range to match the bombers.

Robert McNamara describes LeMay's courage and character, when discussing a report of high abort rate in bomber missions during World War II:

One of the commanders was Curtis LeMay—Colonel in command of a B-24 group. He was the finest combat commander of any service I came across in war. But he was extraordinarily belligerent, many thought brutal. He got the report. He issued an order. He said, 'I will be in the lead plane on every mission. Any plane that takes off will go over the target, or the crew will be court-martialed.' The abort rate dropped overnight. Now that's the kind of commander he was.[2]

In August 1944, LeMay transferred to the China-Burma-India theater and directed first the XX Bomber Command in China and then the XXI Bomber Command in the Pacific. LeMay was later placed in charge of all strategic air operations against the Japanese home islands.

LeMay soon concluded that the techniques and tactics developed for use in Europe against the Luftwaffe were unsuitable against Japan. His bombers flying from China were dropping their bombs near their targets only 5% of the time. Operational losses of aircraft and crews were unacceptably high owing to Japanese daylight air defenses and continuing mechanical problems with the B-29. In January 1945 LeMay was transferred from China to relieve Brig. Gen. Haywood S. Hansell as commander of the XXI Bomber Command in the Marianas.

He became convinced that high-altitude precision bombing would be ineffective, given the usual cloudy weather over Japan. Because Japanese air defenses made daytime bombing below jet stream altitudes too perilous, LeMay finally switched to low-altitude nighttime incendiary attacks on Japanese targets, a tactic senior commanders had been advocating for some time. Japanese cities were largely constructed of combustible materials such as wood and paper. Precision high-altitude daylight bombing was ordered to proceed only when weather permitted or when specific critical targets were not vulnerable to area bombing.

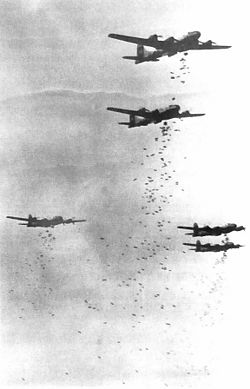

LeMay commanded subsequent B-29 Superfortress combat operations against Japan, including the massive incendiary attacks on 64 Japanese cities. This included the firebombing of Tokyo on March 9–10, 1945, the most destructive bombing raid of the war.[3] For this first attack, LeMay ordered the defensive guns removed from 325 B-29s, loaded each plane with Model E-46 incendiary clusters, magnesium bombs, white phosphorus bombs, and napalm and ordered the bombers to fly in streams at 5,000 to 9,000 feet over Tokyo.

The first pathfinder planes arrived over Tokyo just after midnight on March 10. Following British bombing practice, they marked the target area with a flaming "X." In a three-hour period, the main bombing force dropped 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs, killing some 100,000 civilians, destroying 250,000 buildings and incinerating 16 square miles (41 km2) of the city. Aircrews at the tail end of the bomber stream reported that the stench of burned human flesh permeated the aircraft over the target.[4]

The New York Times reported at the time, "Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, commander of the B-29s of the entire Marianas area, declared that if the war is shortened by a single day, the attack will have served its purpose."

Precise figures are not available, but the firebombing bombing campaign against Japan, directed by LeMay between March 1945 and the Japanese surrender in August 1945, may have killed more than 500,000 Japanese civilians and left 5 million homeless.[5] Official estimates from the United States Strategic Bombing Survey put the figures at 220,000 people killed.[3] Some 40% of the built-up areas of 66 cities were destroyed, including much of Japan's war industry.[3]

The remaining Allied prisoners of war in Japan who had survived imprisonment to that time were frequently subjected to additional reprisals and torture after an air raid. The massive bombing also hit a number of prisons and directly killed a number of allied war prisoners. LeMay was quite aware of the Japanese opinion of him: He once remarked that had the U.S. lost the war, he fully expected to be tried for war crimes, especially in view of Japanese executions of uniformed American flight crews during the 1942 Doolittle raid. He argued that it was his duty to carry out the attacks in order to end the war as quickly as possible, sparing further loss of life.

Presidents Roosevelt and Truman justified these tactics by referring to an estimate of one million Allied casualties if Japan had to be invaded. Additionally, the Japanese had intentionally decentralized 90 percent of their war-related production into small subcontractor workshops in civilian districts, making remaining Japanese war industry largely immune to conventional precision bombing with high explosives.[6]

As the fire bombing campaign took effect, Japanese war planners were forced to expend significant resources to relocate vital war industries to remote caves and mountain bunkers, reducing production of war material. As an officer who served under LeMay, Lieutenant Colonel Robert McNamara was in charge of evaluating the effectiveness of American bombing missions. Later McNamara, as secretary of defense under Kennedy and Johnson, would often clash with LeMay.

LeMay also oversaw Operation Starvation, aerial mining operations against Japanese waterways and ports that disrupted Japanese shipping and food distribution. Although his superiors were unsupportive of this naval objective, LeMay gave it a high commitment level by assigning the entire 313th Bombardment Wing (four groups, about 160 planes) to the task. Aerial mining supplemented a tight Allied submarine blockade of the home islands, drastically reducing Japan's ability to supply its overseas forces to the point that postwar analysis concluded that it could have defeated Japan on its own had it begun earlier.

Cold War

After World War II, LeMay was briefly transferred to The Pentagon as deputy chief of Air Staff for Research & Development. In 1947, he returned to Europe as commander of USAF Europe, heading operations for the Berlin Airlift in 1948 in the face of a blockade by the Soviet Union and its satellite states that threatened to starve the civilian population of the Western occupation zones of Berlin. Under LeMay's direction, C-54 cargo planes that could each carry 10 tons of cargo began supplying the city on July 1. By the fall, the airlift was bringing in an average of 5,000 tons of supplies a day. The airlift continued for 11 months—213,000 flights that brought in 1.7 million tons of food and fuel to Berlin. Faced with the failure of their blockade, the Soviet Union relented and reopened land corridors to the West. Though LeMay is publicly credited with the success of the Berlin Airlift, it was, in fact, orchestrated by General Lucius D. Clay and successfully implemented by Lt. General William H. Tunner, as pointed out in Andrei Cherny's 2008 book, The Candy Bombers: The Untold Story of the Berlin Airlift and America's Finest Hour. However, as Cherny points out in his book, LeMay, who headed the operations for the Airlift, was happy to take the credit, particularly after it became an international success.

In 1948, he returned to the U.S. to head the Strategic Air Command (SAC), replacing Gen George Kenney. When he took over SAC, it consisted of little more than a few understaffed B-29 bombardment groups left over from World War II. Less than half of the available aircraft were operational, and the crews were undertrained. When he ordered a mock bombing exercise on Dayton, Ohio, most bombers missed their targets by one mile or more. "We didn't have one crew, not one crew, in the entire command who could do a professional job"[7] noted LeMay.

In 1952 the 1st Missile Division was activated, having operational control over strategic missiles.

Upon receiving his fourth star in 1951 at age 44, LeMay became the youngest four-star general in American history since Ulysses S. Grant and was the youngest four-star general in modern history as well as the longest serving in that rank.[8] In 1956 and 1957 LeMay implemented tests of 24-hour bomber and tanker alerts, keeping some bomber forces ready at all times. LeMay headed SAC until 1957, overseeing its transformation into a modern, efficient, all-jet force. LeMay's tenure was the longest over a military command in close to 100 years.[9]

Despite popular claims that LeMay advanced the notion of preventive nuclear war, the historical record indicates LeMay actually advocated justified preemptive nuclear war. Several documents dating from the period during which he commanded SAC show LeMay advocating preemptive attack of the Soviet Union, had it become clear the Soviets were preparing to attack SAC and/or the United States. In these documents, which were often the transcripts of speeches before groups such as the National War College or events such as the 1955 Joint Secretaries Conference at the Quantico Marine Corps Base, LeMay clearly advocated using SAC as a preemptive weapon if and when such was necessary. Little evidence suggests LeMay ever advocated unauthorized or unjustified nuclear attack of the Soviet Union. To the contrary, a December 1949 letter from LeMay to the Air Force Chief of Staff Hoyt Vandenberg indicates LeMay was concerned with having explicit authority from the nation's political leadership to launch a preemptive strike against the Soviet Union. This letter, in LeMay's files at the Library of Congress, indicates LeMay was not willing to operate outside the authority afforded him as a military officer and that LeMay also recognized the constitutional role political leadership played in the decision to initiate war.

One apocryphal story has it that he approached a fully fueled bomber with his ever-present cigar stuck firmly between his lips. When asked by a guard to put it out as it might ignite the fuel, LeMay growled, "It wouldn't dare." The line is actually a scene from the 1955 film Strategic Air Command. Actor Frank Lovejoy, playing General Ennis Hawkes (very clearly modeled on LeMay), is smoking around a Boeing C-97 transport and a guard expresses concern that there might be a fire. Lt Col "Dutch" Holland (played by James Stewart) simply smiles and says, "It wouldn't dare."

The “Airpower Battle”

General LeMay was instrumental in the U.S. Air Force's acquisition of a large fleet of new strategic bombers, establishment of a vast aerial refueling system, the formation of many new units and bases, development of a strategic ballistic missile force, and establishment of a strict command and control system with an unprecedented readiness capability. He insisted on rigorous training and very high standards of performance for his aircrews, supposedly saying, "I have neither the time nor the inclination to differentiate between the incompetent and the merely unfortunate."

On LeMay's departure, SAC was composed of 224,000 airmen, close to 2,000 heavy bombers, and nearly 800 tanker aircraft.[9]

LeMay was an active amateur radio operator and held a succession of call signs; K0GRL, K4FRA, and W6EZV. He held these calls respectively while stationed at Offutt AFB, Washington, D.C. and when he retired in California. K0GRL is still the call sign of the Strategic Air Command Memorial Amateur Radio Club.[10] He was famous for being on the air on amateur bands while flying on board SAC bombers. LeMay became aware that the new single sideband (SSB) technology offered a big advantage over Amplitude Modulation (AM) for SAC aircraft operating long distances from their bases. In conjunction with Art Collins (W0CXX) of Collins Radio, he established SSB as the radio standard for SAC bombers in 1957.[11]

LeMay was appointed Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force in July 1957, serving until 1961, when he was made the fifth Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force on the retirement of Gen Thomas White. His belief in the efficacy of strategic air campaigns over tactical strikes and ground support operations became Air Force policy during his tenure as chief of staff.

As chief of staff, LeMay clashed repeatedly with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Air Force Secretary Eugene Zuckert, and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Army general Maxwell Taylor. At the time, budget constraints and successive nuclear war fighting strategies had left the armed forces in a state of flux. Each of the armed forces had gradually jettisoned realistic appraisals of future conflicts in favor of developing its own separate nuclear and nonnuclear capabilities. At the height of this struggle, the U.S. Army had even reorganized its combat divisions to fight land wars on irradiated nuclear battlefields, developing short-range atomic cannon and mortars in order to win appropriations. The United States Navy in turn proposed delivering strategic nuclear weapons from supercarriers intended to sail into range of the Soviet air defense forces. Of all these various schemes, only LeMay's command structure of SAC survived complete reorganization in the changing reality of postwar conflicts.

Though LeMay lost significant appropriation battles for the Skybolt ALBM and the B-52 Stratofortress replacement, the XB-70 Valkyrie, he was largely successful at expanding Air Force budgets. He advocated the introduction of satellite technology and pushed for the development of the latest electronic warfare techniques. By contrast, the U.S. Army and Navy frequently suffered budgetary cutbacks and program cancellations by Congress and Secretary McNamara.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, LeMay clashed again with U.S. President John F. Kennedy and Defense Secretary McNamara, arguing that he should be allowed to bomb nuclear missile sites in Cuba. He opposed the naval blockade and, after the end of the crisis, suggested that Cuba be invaded anyway, even after the Russians agreed to withdraw. LeMay called the peaceful resolution of the crisis "the greatest defeat in our history".[12] Unknown to the U.S., the Soviet field commanders in Cuba had been given authority to launch—the only time such authority was delegated by higher command.[13] They had twenty nuclear warheads for medium-range R-12 ballistic missiles capable of reaching U.S. cities (including Washington) and nine tactical nuclear missiles. If Soviet officers had launched them, many millions of U.S. citizens would have been killed. The ensuing SAC retaliatory thermonuclear strike would have killed roughly one hundred million Soviet citizens, and brought nuclear winter to much of the Northern Hemisphere. Kennedy refused LeMay's requests, however, and the naval blockade was successful.[13]

LeMay's dislike for tactical aircraft and training backfired in the low-intensity conflict of Vietnam, where existing Air Force interceptor aircraft and standard attack profiles proved incapable of carrying out sustained tactical bombing campaigns in the face of hostile North Vietnamese antiaircraft defenses. LeMay said, "Flying fighters is fun. Flying bombers is important."[14] Aircraft losses on tactical attack missions soared, and Air Force commanders soon realized that their large, missile-armed aircraft were exceedingly vulnerable not only to antiaircraft shells and missiles but also to cannon-armed, maneuverable Soviet fighter jets.

LeMay advocated a sustained strategic bombing campaign against North Vietnamese cities, harbors, ports, shipping, and other strategic targets. His advice was ignored. Instead, an incremental policy was implemented that focused on limited interdiction bombing of fluid enemy supply corridors in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. This limited campaign failed to destroy significant quantities of enemy war supplies or diminish enemy ambitions. Bombing limitations were imposed by President Lyndon Johnson for geopolitical reasons, as he was afraid that bombing Soviet and Chinese ships in port and killing Soviet advisers would bring the Soviets more directly into the war and destabilize the European Cold War.

Some military historians have argued that LeMay's theories were eventually proven correct. Near the war's end in December 1972, President Richard Nixon ordered Operation Linebacker II, a high-intensity Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps aerial bombing campaign, which included hundreds of B-52 bombers that succeeded in widespread destruction of previously untouched North Vietnamese strategic targets. The intense bombing compelled the communist government to quickly conclude negotiations that finally ended America's longest war. Others believe the impact was smaller, as the peace negotiations were only temporarily stalled and the North Vietnamese were trying to get better terms.

The memorandum from LeMay, Chief of Staff, USAF, to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, January 4, 1964, illustrates LeMay's thinking: "It is important to recognize, however, that ballistic missile forces represent both the U.S. and Soviet potential for strategic nuclear warfare at the highest, most indiscriminate level, and at a level least susceptible to control. The employment of these weapons in lower level conflict would be likely to escalate the situation, uncontrollably, to an intensity which could be vastly disproportionate to the original aggravation. The use of ICBMs and SLBMs is not, therefore, a rational or credible response to provocations which, although serious, are still less than an immediate threat to national survival. For this reason, among others, I consider that the national security will continue to require the flexibility, responsiveness, and discrimination of manned strategic weapon systems throughout the range of cold, limited, and general war."[15]

Additional evidence of LeMay's thinking is that in his 1965 autobiography, co-written with MacKinlay Kantor, LeMay is quoted as saying his response to North Vietnam would be to demand that "they’ve got to draw in their horns and stop their aggression, or we’re going to bomb them back into the Stone Age. And we would shove them back into the Stone Age with Air power or Naval power–not with ground forces."

Post-military career

Owing to his unrelenting opposition to the Johnson administration's Vietnam policy and what was widely perceived as his hostility to Secretary McNamara, LeMay was essentially forced into retirement in February 1965 and seemed headed for a political career. Moving to California, he was approached by conservatives to challenge moderate Republican Thomas Kuchel for his seat in the United States Senate in 1968, but he declined. For the presidential race that year, LeMay originally supported Richard Nixon; he turned down two requests by George Wallace to join his American Independent Party that year on the grounds that a third-party candidacy might hurt Nixon's chances at the polls. (By coincidence, Wallace had served as a sergeant in a unit commanded by LeMay during World War II.) However, LeMay gradually became convinced that Nixon planned to pursue a conciliatory policy with the Soviets and accept nuclear parity rather than retain America's first-strike supremacy. Consequently LeMay, being fully aware of Wallace's segregationist platform and undeterred by his racist intentions, decided to throw his support to Wallace and eventually became Wallace's running mate. The general was dismayed, however, to find himself attacked in the press as a racial segregationist because he was running with Wallace; he had never considered himself a bigot. When Wallace announced his selection in October 1968, LeMay opined that he, unlike many Americans, clearly did not fear using nuclear weapons. His saber rattling did not help the Wallace campaign.

During the 1968 campaign, LeMay became widely associated with the "Stone Age" comment, especially because he had suggested use of nuclear weapons as a strategy to quickly resolve a deeply protracted conventional war which eventually claimed over 50,000 American plus millions of Vietnamese lives. This reputation did nothing to diminish perceptions of extremism in the Wallace-LeMay ticket. General LeMay disclaimed the comment, saying in a later interview: “I never said we should bomb them back to the Stone Age. I said we had the capability to do it."

The Wallace-LeMay AIP ticket received 13.5 percent of the popular vote, higher than most third-party candidacies in the United States, and carried 5 states for a total of 46 electoral votes, but this was not enough to deny Nixon his election as 37th President of the United States. Following the 1968 election, LeMay returned to private life, including pursuing several charitable projects. He declined further suggestions to run for political office.

He was honored by several countries, receiving the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters, the Distinguished Flying Cross with two oak leaf clusters, the Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal with two oak leaf clusters, the French Legion of Honor and the Silver Star. On December 7, 1964 the Japanese government conferred on him the First Order of Merit with the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun. He was elected to the Alfalfa Club in 1957 and served as a general officer for twenty-one years.

Death

He died on October 1, 1990, at March Air Force Base in Riverside County, California, and is buried in the United States Air Force Academy Cemetery [16] at Colorado Springs, Colorado. He was survived by his wife, Helen, who died in 1994.

Miscellany

LeMay and UFOs

The April 25, 1988 issue of The New Yorker carried an interview with retired Air Force Reserve Major General and former U.S. Senator from Arizona, Barry Goldwater, who said he repeatedly asked his friend General LeMay if he (Goldwater) might have access to the secret "Blue Room" at Wright Patterson Air Force Base, alleged by numerous Goldwater constituents to contain UFO evidence. According to Goldwater, an angry LeMay gave him "holy hell" and said, "Not only can't you get into it but don't you ever mention it to me again."

LeMay and sports car racing

General LeMay was also a sports car owner and enthusiast (he owned an Allard J2); as the "SAC era" began to wind down, LeMay loaned out facilities of SAC bases for use by the Sports Car Club of America,[17] as the era of early street races began to die out. He was awarded the Woolf Barnato Award, SCCA's highest award for contributions to the Club, in 1954.[17] In November 2006, it was announced that General LeMay would be one of the inductees into the SCCA Hall of Fame in 2007.[17]

Air Force Academy Exemplar

On March 13, 2010, LeMay was named the exemplar for the United States Air Force Academy class of 2013.

Rank history

Curtis LeMay’s first contact with military service occurred in September 1924 when he enrolled as a student in the ROTC program at Ohio State University. By his senior year, LeMay was listed on the ROTC rolls as a "cadet lieutenant colonel" but had not actually received an appointment in the regular United States military.

On June 14, 1928, the summer before the start of his senior year, LeMay accepted a commission as a second lieutenant in the Field Artillery Reserve of the United States Army. In September 1928, LeMay was approached by the Ohio National Guard and asked to accept a state commission, also as a second lieutenant, which LeMay accepted. This created a unique situation in LeMay's service record since in 1928 it was unusual for a person to hold a commission both in the National Guard and the Army Reserve.

On September 29, 1928, LeMay enlisted in the Army Air Corps as an aviation cadet under the service number 6650359. For the next 13 months, LeMay was not only on the enlisted rolls of the Regular Army but also still held a commission in the National Guard and Army Reserve. Thus, for this short period in LeMay’s career, he was technically an officer and enlisted soldier at the same time, a practice no longer permitted in the U.S. military. The matter was resolved on October 2, 1929, when LeMay’s Guard and Reserve commission were terminated. According to his service record, these commissions were revoked "by telephone" after an Army personnel officer, realizing that LeMay was holding officer and enlisted status simultaneously, called him to discuss the matter.

On October 12, 1929, LeMay finished his flight training and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Air Corps Reserve. This was the third time he had been appointed a second lieutenant in just under two years. He held this reserve commission until June 1930, when he was appointed as a Regular Army officer in the Air Corps.

LeMay experienced slow advancement throughout the 1930s, as did most officers of the seniority-driven regular army. By 1940, he was still a captain but, beginning in 1941, began to receive temporary advancement in grade in the expanding Army Air Forces. LeMay advanced from captain to brigadier general in three years and by 1944 was a major general. When World War II ended, he was appointed to the permanent rank of brigadier general in the Regular Army but held his temporary rank of major general in the Army until promotion to lieutenant general in the now separate United States Air Force in 1948. He then was promoted to full general in 1951 and held this rank until his retirement in 1965.

Dates of rank

- Army ROTC Cadet: September 1924

- Second Lieutenant, Field Artillery Reserve: June 14, 1928

- Second Lieutenant, Ohio National Guard: September 22, 1928

- Flying Cadet, Army Air Corps: September 28, 1928

- Officer Commissions Terminated: October 2, 1929

- Second Lieutenant, Air Corps Reserve: October 12, 1929

- Second Lieutenant, Army Air Corps: February 1, 1930

- First Lieutenant, Army Air Corps: March 12, 1935

- Captain, Army Air Corps: January 26, 1940

- Major, Army Air Corps: March 21, 1941

- Lieutenant Colonel, Army of the United States: January 23, 1942

- Colonel, Army of the United States: June 17, 1942

- Brigadier General, Army of the United States: September 28, 1943

- Permanent in the Regular Army: June 22, 1946

- Major General, Army of the United States: March 3, 1944

- Lieutenant General, United States Air Force: January 26, 1948

- General, United States Air Force: October 29, 1951

- General, USAF (Retired): February 1, 1965

Further promotion

According to letters in Curtis LeMay's service record, while he was in command of SAC during the 1950s several petitions were made by Air Force service members to have LeMay promoted to the rank of General of the Air Force. The Air Force leadership, however, felt that such a promotion would lessen the prestige of this rank, which was seen as a wartime rank to be held only in times of extreme national emergency.

Per the Chief of the Air Force General Officers Branch, in a letter dated February 28, 1962:

It is clear that a grateful nation, recognizing the tremendous contributions of the key military and naval leaders in World War II, created these supreme grades as an attempt to accord to these leaders the prestige, the clear-cut leadership, and the emolument of office befitting their service to their country in war. It is the conviction of the Department of the Air Force that this recognition was and is appropriate. Moreover, appointments to this grade during periods other than war would carry the unavoidable connotation of downgrading of those officers so honored in World War II.

Thus, no serious effort was ever made to promote LeMay to the rank of General of the Air Force, and the matter was eventually dropped after his retirement from active service in 1965.

Awards and decorations

LeMay received recognition for his work from thirteen countries, receiving twenty-two medals and decorations.

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

Works

Books

- (with MacKinlay Kantor) Mission with LeMay: My Story (Doubleday, 1965) ISBN B00005WGR2

- (with Dale O. Smith) America is in Danger (Funk & Wagnalls, 1968) ISBN B00005VCVX

- (with Bill Yenne) Superfortress: The Story of the B-29 and American Air Power (McGraw-Hill, 1988) ISBN 0-07-037160-1

Film and television appearances

- The Last Bomb (documentary, 1945)

- In the Year of the Pig (documentary, 1968)

- The World at War (documentary TV series, 1974)

- Race for the Superbomb (documentary, 1999)

- JFK (film, 1991; featured in archival footage)

- Roots of the Cuban Missile Crisis (documentary, 2001)

- The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (documentary, 2003)

- DC3:ans Sista Resa (Swedish documentary, 2004)

In popular culture

- Above and Beyond – LeMay is portrayed by Jim Backus (film, 1952)

- Strategic Air Command – the character of General Ennis C. Hawkes, based on LeMay, is played by Frank Lovejoy (film, 1955)

- Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb – the character of General Buck Turgidson, played by George C. Scott, is based in part on LeMay (film, 1964)[18]

- The Missiles of October – LeMay is played by Robert P. Lieb (TV, 1974)[19]

- Enola Gay: The Men, the Mission, the Atomic Bomb – LeMay is portrayed by Than Wyenn (TV, 1980)

- Kennedy – played by Barton Heyman (TV series, 1983)[19]

- Race for the Bomb – played by Lloyd Bochner (TV series, 1987)[19]

- Hiroshima played by Cedric Smith (TV, 1995)[19]

- Thirteen Days – LeMay is played by Kevin Conway (film, 2000)[19]

- Roots of the Cuban Missile Crisis – played by Kevin Conway (video, 2001)[19]

References

Notes

- ↑ Harper, C.B. (Red). "March 1944 and Berlin". With The Mighty Eighth And The Fifteenth Air Forces In Action Over Europe In World War II. http://www.buffalogal.org/MarchBerliln.htm.

- ↑ Errol Morris, The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, Documentary Film, 2003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Summary Report (Pacific War). Washington D.C. July 1, 1946.

- ↑ Buckley, John. Air Power in the Age of Total War. Indiana University Press, 1999, p. 193. ISBN 025321324X

- ↑ Bradley, F. J. No Strategic Targets Left. "Contribution of Major Fire Raids Toward Ending WWII", Turner Publishing Company, limited edition. ISBN 1-56311-483-6. p. 38.

- ↑ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945, Random House, 1970, p. 671.

- ↑ Ford, Daniel (April 01, 1996). "History of Flight—B-36: Bomber at the Crossroads". Air & Space Magazine. http://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/B-36-Bomber-at-the-Crossroads.html?c=y&page=5.

- ↑ "Warrenkozak.com, LeMay: The Life And Wars Of General Curtis LeMay". WarrenKozak. http://www.warrenkozak.com/basics.html. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 AIR FORCE Magazine. October 2008.

- ↑ "Surfin': More Hamming at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue". National Association for Amateur Radio. http://www.arrl.org/news/features/2005/02/18/1/.

- ↑ "Amateur Radio and the Rise of SSB" (PDF). National Association for Amateur Radio. http://www.arrl.org/qst/2003/01/McElroy.pdf.

- ↑ Feltus, Pamela. "Curtis E. LeMay". Centennial of Flight. U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Air_Power/LeMay/AP36.htm. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rhodes, 1995, pp. 574–576

- ↑ Robert Coram, “Boyd. Back Bay Books/Little, Brown, and Company, 2002, p. 59.

- ↑ National Archives and Records Administration, RG 200, Defense Programs and Operations, LeMay's Memo to President and JCS Views, Box 83. Secret.

- ↑ "Curtis Emerson LeMay". Find-A-Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=9654. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "SCCA Announces 2007 Hall of Fame Class". Sports Car Club of America. November 22, 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. http://web.archive.org/web/20061205225745/http://www.scca.com/News/News.asp?Ref=729.

- ↑ Carter, Dan T. (1995). The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 357. ISBN 0807125970. "

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 "General Curtis LeMay (character)" on Internet Movie Database

Bibliography

- Atkins, Albert Air Marshall Sir Arthur Harris and General Curtis E. Lemay: A Comparative Analytical Biography. AuthorHouse, 2001. ISBN 0-7596-5940-0.

- Craig, William The Fall of Japan. The Dial Press, 1967. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 67-10704.

- Coffey, Thomas M. Iron Eagle: The Turbulent Life of General Curtis LeMay. Random House, 1986. ISBN 0-517-55188-8.

- Kozak, Warren LeMay: The Life and Wars of Curtis LeMay. Regnery, 2009.

- LeMay, Curtis E. "Mission with LeMay: My Story". Doubleday, 1965

- LeMay, Curtis E., Yenne, Bill Superfortress: The Boeing B-29 and American Airpower in World War II. Westholme Publishing 2006, originally published by Berkley, 1988

- McNamara, Robert S. In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. Vintage Press, 1995. ISBN 0-679-76749-5.

- Moscow, Warren "City’s Heart Gone". The New York Times. March 11, 1945: 1, 13.

- Narvez, Alfonso A. "Gen. Curtis LeMay, an Architect of Strategic Air Power, Dies at 83". The New York Times. October 2, 1990.

- Allison, Graham. Essence of Decision:Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (1971 – updated 2nd edition, 1999). Longman. ISBN 0-321-01349-2.

- Rhodes, Richard Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0-684-80400-X

- Tillman, Barrett. LeMay. Palgrave's Great Generals Series, 2007. ISBN 1-4039-7135-8

- USAF National Museum, "Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, Awards and Decorations"

- USAF Service Record of Curtis LeMay, Military Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, MO

- 456 Fighter Interceptor Squadron webpage

External links

- Air Force Magazine bio of LeMay, March 1998

- Bio from American Airpower Biography: A Survey of the Field by Colonel Phillip S. Meilinger, USAF

- Richard Rhodes on: General Curtis LeMay, Head of Strategic Air Command

- Richard Rhodes on: LeMay's Vision of War

- Annotated bibliography of Curtis LeMay from the Alsos Digital Library

- Gen. Curtis E. LeMay bio on USAF National Museum site

- With the Possum and the Eagle, by Ralph H. Nutter. A view of working with LeMay, by his lead navigator in Europe.

- "Curtis LeMay". Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=9654. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||